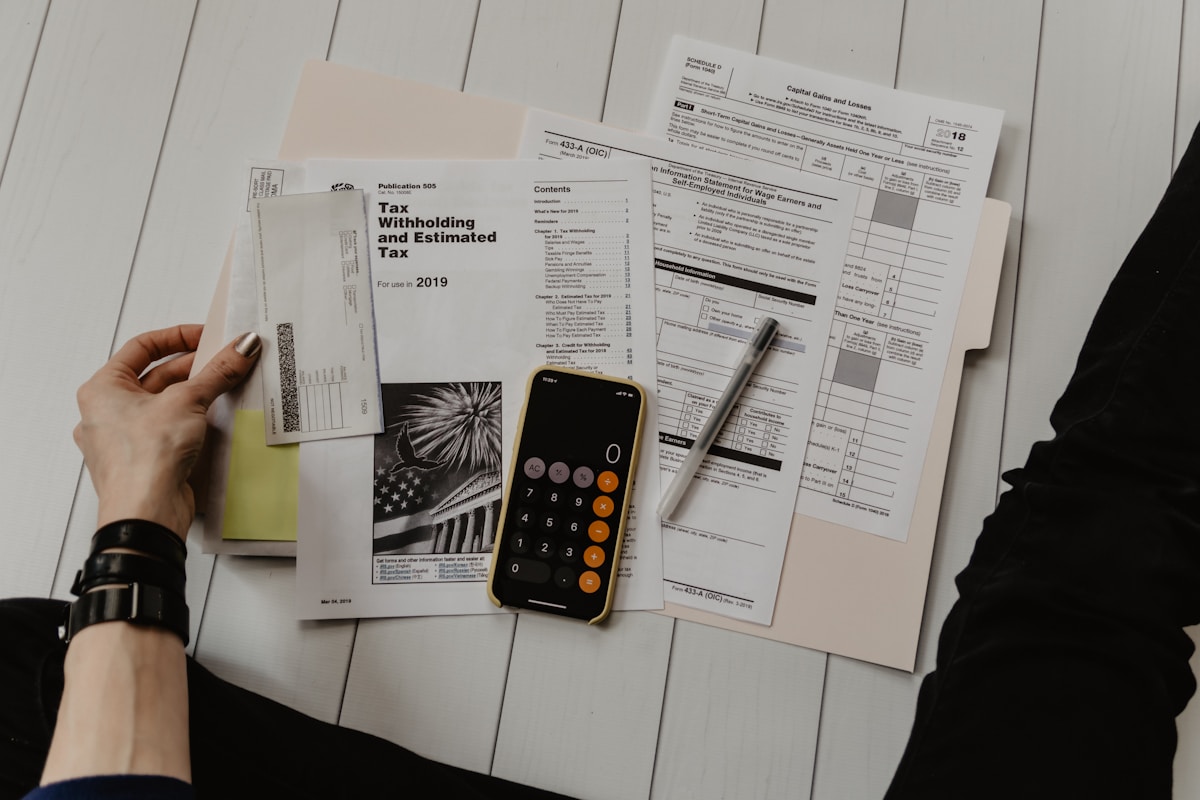

Roth vs Traditional Retirement Accounts: The Ultimate Comparison Guide

One of the most consequential decisions in retirement planning is choosing between Roth and traditional retirement accounts. Both offer tax advantages, but the timing of those advantages differs dramatically. Making the right choice—or the right combination—can save you thousands of dollars over your lifetime. This guide breaks down everything you need to know to make an informed decision for your specific situation.

Understanding the Fundamental Difference

Traditional retirement accounts (Traditional IRAs and Traditional 401(k)s) offer tax-deferred growth. You contribute pre-tax dollars, reducing your current taxable income. The money grows without annual taxation. However, every dollar withdrawn in retirement counts as taxable income at your ordinary rates.

Roth accounts (Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k)s) flip this equation. You contribute after-tax dollars, receiving no current tax deduction. The money grows tax-free. Qualified withdrawals in retirement come out completely tax-free—you never pay taxes on the growth.

The core question is whether you’re better off paying taxes now (Roth) or later (Traditional). The answer depends on your current tax rate, your expected retirement tax rate, and several other factors we’ll explore.

When Traditional Accounts Make Sense

If your current tax rate exceeds your expected retirement tax rate, traditional accounts typically win mathematically. The tax savings from deducting contributions now outweigh the eventual taxes on withdrawals.

High earners in peak earning years often fall into this category. Someone in the 32% bracket today who expects to drop to the 22% bracket in retirement saves 10 cents on every dollar contributed and eventually withdrawn. Over decades of contributions, this adds up significantly.

Traditional accounts also make sense when you need the current tax deduction to afford contributions. If your budget is tight, the tax savings from a traditional contribution might be the difference between saving adequately and falling short.

Those expecting significant pension income or Social Security might prefer Roth accounts, however, since those income sources could push them into higher brackets even after retiring from active employment.

When Roth Accounts Shine

Younger workers early in their careers often benefit most from Roth contributions. In lower tax brackets today, they pay relatively little tax on contributions. Decades of tax-free growth compound dramatically, and qualified withdrawals remain untaxed regardless of future rate increases.

Those who believe tax rates will rise generally should favor Roth accounts. Given current deficit levels and demographic pressures from an aging population, many financial planners expect higher rates in the future. Roth contributions lock in today’s relatively low rates.

Roth accounts provide valuable flexibility in retirement. Since qualified withdrawals don’t count as taxable income, they don’t trigger Social Security taxation thresholds, Medicare premium surcharges, or other income-based phase-outs that traditional withdrawals might.

Estate planning considerations favor Roth accounts as well. While traditional IRAs saddle heirs with required minimum distributions that generate taxable income, Roth IRAs pass tax-free to beneficiaries (though the SECURE Act now requires most non-spouse beneficiaries to empty inherited IRAs within ten years).

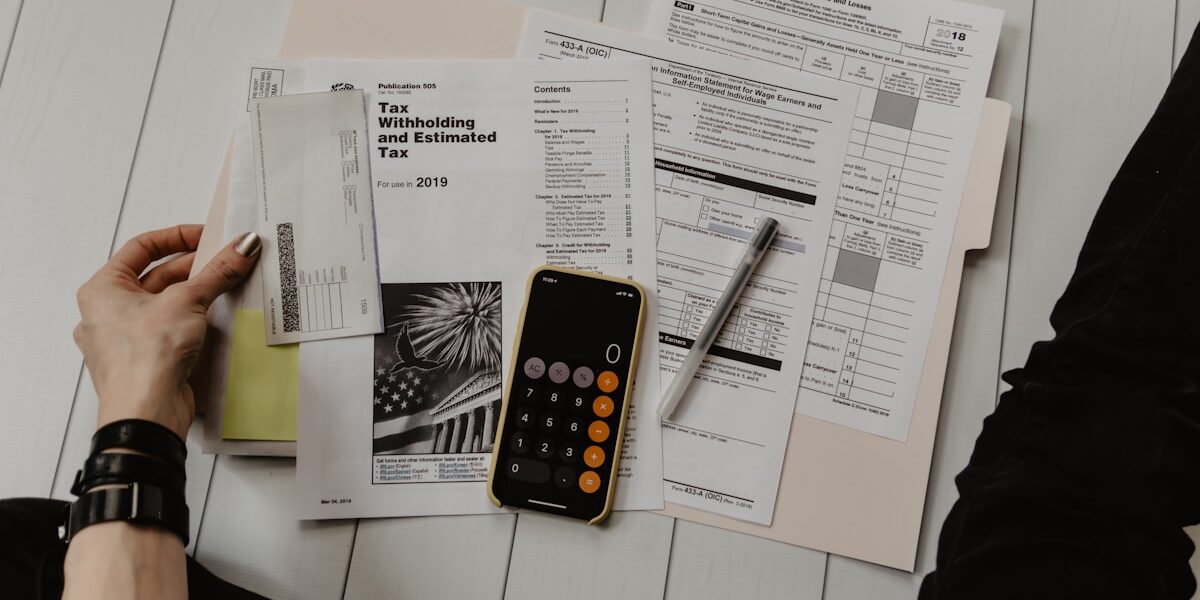

The Case for Diversification

Many financial advisors recommend contributing to both account types rather than choosing exclusively one or the other. This tax diversification provides flexibility to optimize withdrawals in retirement based on circumstances you can’t fully predict today.

Consider someone with equal balances in Traditional and Roth accounts at retirement. In a year with high medical expenses, they might withdraw from the Traditional account to take advantage of the medical expense deduction. In a year they’re selling a vacation property for a significant gain, they might draw from the Roth to avoid pushing themselves into higher brackets.

Life changes unpredictably. Tax laws evolve constantly. Having both account types provides options regardless of how circumstances unfold.

Contribution Limits and Income Restrictions

Understanding the rules governing each account type is essential for effective planning. The limits and restrictions differ between IRAs and employer plans, and between Traditional and Roth versions.

For 2025, IRA contribution limits stand at $7,000 annually ($8,000 for those 50 and older). This combined limit applies across all your IRAs—you can’t contribute $7,000 to a Traditional IRA and another $7,000 to a Roth IRA in the same year.

Traditional IRA deductions phase out for those covered by workplace retirement plans above certain income thresholds. Roth IRA contributions have their own income limits—high earners may be ineligible to contribute directly.

The backdoor Roth IRA strategy allows high earners to work around Roth contribution limits. You contribute to a Traditional IRA (without deduction) and immediately convert to Roth. While legal and commonly used, this strategy requires careful execution to avoid unintended tax consequences.

Employer plans like 401(k)s have higher contribution limits—$23,500 for 2025 ($31,000 for those 50+). Many employers now offer both Traditional and Roth 401(k) options. Unlike Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k)s have no income limits—anyone can contribute regardless of earnings.

The Roth Conversion Strategy

Roth conversions allow you to move money from Traditional accounts to Roth accounts, paying taxes on the converted amount in the year of conversion. This strategy can make sense in several scenarios.

During low-income years—perhaps due to job transition, early retirement before Social Security begins, or economic downturns—converting fills up lower tax brackets efficiently. You pay tax at rates lower than you’d face in future Required Minimum Distribution years.

After significant market declines, converting allows you to pay taxes on depressed values. When the market recovers, that growth occurs inside your Roth, forever tax-free.

Managing Required Minimum Distributions through gradual conversions before age 73 can reduce future taxable income. Large traditional balances lead to large RMDs that can push retirees into higher brackets and trigger Social Security taxation.

However, conversions require available cash to pay the resulting taxes. Using IRA funds to pay conversion taxes undermines the strategy’s benefits. Plan conversions when you have non-retirement funds available for the tax bill.

Required Minimum Distributions

Traditional retirement accounts require minimum withdrawals beginning at age 73 (increasing to 75 for those born in 1960 or later). These Required Minimum Distributions ensure the government eventually collects taxes on money that’s grown tax-deferred for decades.

RMD amounts are calculated by dividing your account balance by a life expectancy factor published by the IRS. As you age, the factor decreases, requiring larger percentage withdrawals. Failure to take required distributions triggers a 25% penalty on the amount not withdrawn.

Roth IRAs have no RMDs during the owner’s lifetime. You can let the money grow tax-free indefinitely, leaving a larger tax-free inheritance. This alone makes Roth accounts valuable for those who don’t need all their retirement funds for living expenses.

Note that Roth 401(k)s previously required RMDs, but legislation passed in 2022 eliminated this requirement starting in 2024. Rolling Roth 401(k) funds to a Roth IRA is no longer necessary solely to avoid RMDs.

Access Rules and Early Withdrawal Penalties

Understanding when and how you can access funds without penalty matters for liquidity planning.

Traditional account withdrawals before age 59½ generally trigger a 10% early withdrawal penalty in addition to ordinary income taxes. Several exceptions exist: first home purchases (up to $10,000), qualified education expenses, and substantially equal periodic payments, among others.

Roth IRA contributions—not earnings—can be withdrawn at any time without taxes or penalties. You already paid taxes on that money. This makes Roth IRAs useful as backup emergency funds, though depleting contributions undermines long-term growth.

Roth earnings require the account to be at least five years old AND the owner to be over 59½ (or qualify for another exception) for tax-free and penalty-free withdrawal. Earnings withdrawn before meeting both requirements may face taxes and penalties.

Making Your Decision

No single answer suits everyone. Consider these factors when choosing between Traditional and Roth:

Your current marginal tax bracket compared to your expected retirement bracket is the primary consideration. If current rates are higher, lean Traditional. If current rates are lower, lean Roth.

Your time horizon matters. Younger workers with decades until retirement benefit most from Roth’s tax-free growth compounding over time.

State tax considerations play a role too. Some states don’t tax retirement income—moving from a high-tax state during your career to a no-income-tax state in retirement favors Traditional accounts.

Your overall estate plan and desire to leave tax-advantaged assets to heirs may favor Roth contributions.

When genuinely uncertain, splitting contributions between account types provides flexibility and hedges against unpredictable future tax environments.

Conclusion

The Traditional versus Roth decision impacts your financial life for decades. While the math can be complex, understanding the core concepts—current versus future tax rates, the power of tax-free growth, and the flexibility of diversification—enables informed choices. Consider consulting a qualified financial planner or tax professional to model scenarios specific to your situation and optimize your retirement savings strategy.

Stay in the loop

Get the latest wildlife research and conservation news delivered to your inbox.